A History of 3

Stert Street,

Abingdon, UK

Sketch by Ken Messer

Revised March 2015

The site

No 3 Stert Street is in the centre of Abingdon, next door but one to St Nicholas' Church. The site is part of a strip of land that runs north-south from The Vineyard to the church. The eastern boundary was one wall of Abingdon Abbey until the dissolution of the Abbey in 1538, and the western boundary was the river Stert which ran parallel to this wall. The Abbey owned this strip of land. What was on the site before the present house is open to question. There was almost certainly Iron Age occupation because of its position in the centre of the town, and a very limited excavation in 1970 showed slight evidence of Roman occupation as well. We know from the cartularies of Abingdon Abbey that in the 13th and 14th centuries the Abbey built properties along this strip of land, which had previously been 'waste' - that is to say, used for grazing pigs and geese. And we also know from the records of the heads of department of the Abbey (known as Obedientiars) that in the 14th and 15th centuries the Abbey was receiving rent from properties on this land.

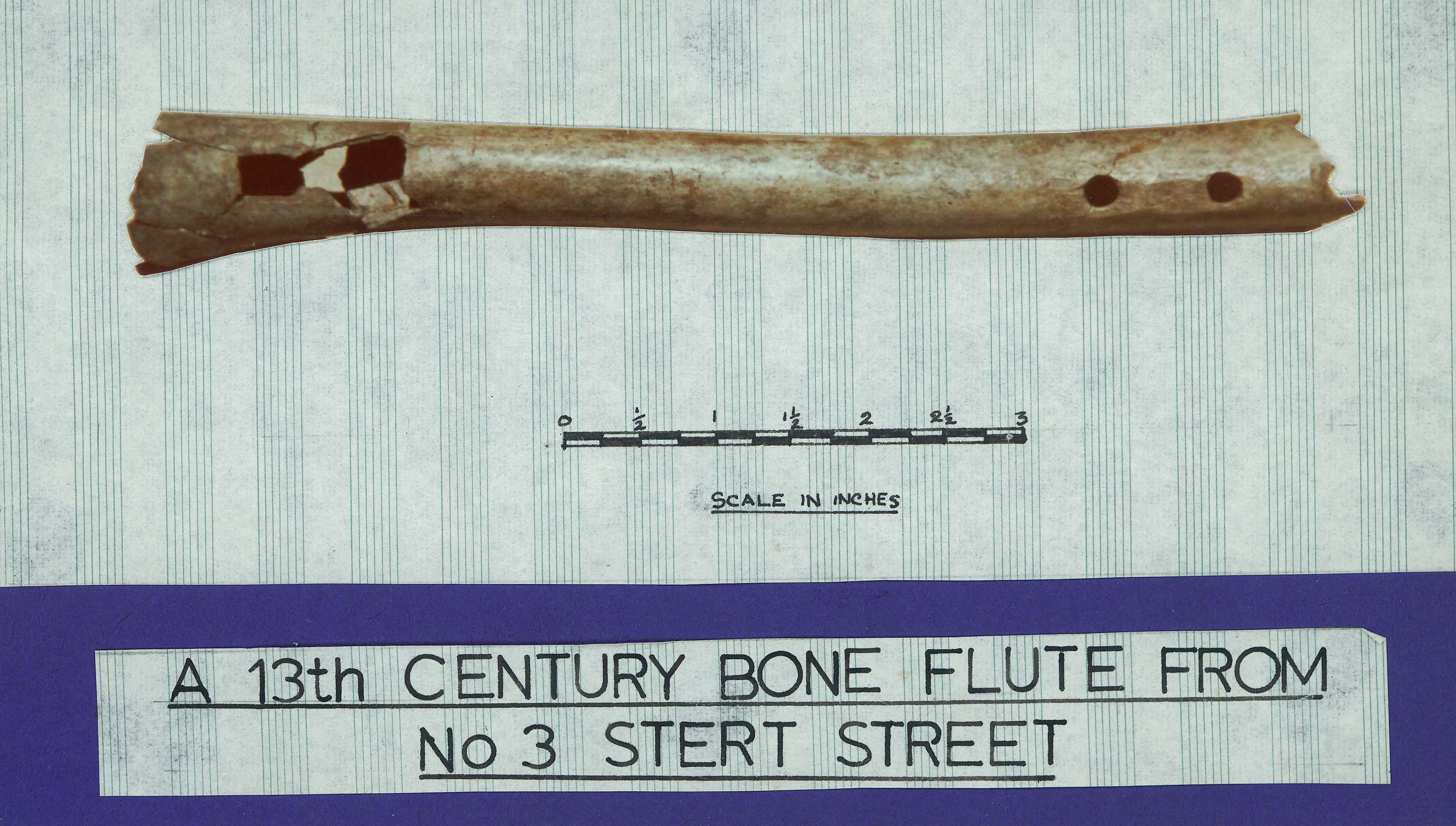

It is very likely that the building preceding the present house was one of the boarding houses for the Grammar School, which itself was next door to St Nicholas' Church. If this was so, it was probably run by one Dionysia Mundy, who paid an annual rent of 18 pence to the Abbey. We do not know what this putative boarding house looked like. The Abingdon Area Archaeological and Historical Society, during its excavation within the old part of the house in 1970, found the remains of a wide 14th-century rubble wall which turned through a right-angle and disappeared under the next-door building (now No 5 Stert Street). Nobody knows of what sort of building this wall was a part. It is about 20 feet back from the line of the front of the present house (but it might not have been the front wall). If this rubble structure was part of Mrs Mundy's boarding house, it is not clear what its function was. It cuts into a 13th century rubbish pit, which suggests that somebody was living on part of the site in the 13th century, and that fits in with what we know about the Abbey building on this land at that time. Within the pit a 13th century bone flute (now in the possession of the Bates Collection) was discovered by the archeology team.

.

Dionysia Mundy's name appears as a tenant in the records of the Fraternity of the Holy Cross in 1430, so if this is the same Dionysia Mundy who was running a school boarding house on this site, it looks as though the property at one time had been sold by the Abbey to the Fraternity and then later taken back again, which is known to have happened to other properties.

Dendrochronological examination has dated the building of the house to between 1466 and 1471 (in those days it was usual to use newly felled trees for construction). The width of the greater part of the building conforms to that specified in the Amyce survey of 1554, which recorded the details of what had been the property of Abingdon Abbey before its dissolution - ie 20 feet. The narrow southern section (which is of the same building date) was at some unknown time absorbed into No 3 from the house next door, making a total present-day width of 28 feet. However, this move did not include the appropriation of the equivalent part of next door's back garden; this irregularity is reflected in the subsequent and present boundary of the site of No 3.

Signs of occupation

In three of the bedrooms there are

several black oval marks well indented into the timber beams. The

largest mark is 2 1/2 inches high and 1/2 inch width. These are taper-marks, and are burns in the wood resulting from

repeated use of rush tapers to provide light. They were fixed to the timber with a

lump of clay.

First major change of ownership

When the Abbey was dissolved in 1538 all its property passed into the ownership of the Crown. The Ministers' Accounts from the Court of Augmentations of the King's Revenue - which evaluated what the King had seized - listed the Abbey tenants living on the east side of Stert Street and recorded what rent they were paying to the Abbey. Although, of course, the houses were not numbered, by simply counting the number of properties along from St Nicholas' Church we can have a pretty good idea of who was the tenant in this house at the time. It was probably Robert Coke, and he was paying a rent of 21 shillings and 4 pence to the Abbey at the time of the Dissolution.

In 1554 Roger Amyce, the King's surveyor, carried out a survey of all the property in Abingdon once owned by the Crown. According to this record the tenant of the house was one William Kysby, and he had paid the same rent to the Abbey as Robert Coke. Kysby came from a clerical family and was twice Mayor of Abingdon, so it may be that No 3 was not grand enough for him to live in himself and he sub-let it. Interestingly, a plan, based on Amyce, in Preston's book on St Nicholas' church shows 103 feet between the house frontage and the line of the Abbey wall, exactly as it is today.

Freehold to the Borough

In 1556 Abingdon received its charter of incorporation from the Crown and the house passed - together with other properties that the Crown had acquired from the Abbey - into the ownership of the borough. It stayed in borough ownership for the next three hundred years and some of the records concerning it have survived in the possession of Abingdon Town Council. After William Kysby there is a gap in the records until John Rice took over the lease in 1670.

A 16th Century wall painting upstairs and 17th Century paneling downstairs

All we know about this missing period is that

in the late 16th or early 17th century the occupier had

enough money to have one of the bedroom walls decorated with

painted strapwork; this was later plastered over but enough survives on

the

timber braces to tell us what the wall was once like. The quality of

this decoration

indicates that the people who commissioned it would have

been prosperous rather than wealthy, and of the merchant or farmer

class. The

faint remains of this early decoration were recently studied by local

artist Liese Cattle who

has re-created (left) both the colours as they once were, and the

basic design, which

had originally been repeated over the whole wall.

All we know about this missing period is that

in the late 16th or early 17th century the occupier had

enough money to have one of the bedroom walls decorated with

painted strapwork; this was later plastered over but enough survives on

the

timber braces to tell us what the wall was once like. The quality of

this decoration

indicates that the people who commissioned it would have

been prosperous rather than wealthy, and of the merchant or farmer

class. The

faint remains of this early decoration were recently studied by local

artist Liese Cattle who

has re-created (left) both the colours as they once were, and the

basic design, which

had originally been repeated over the whole wall.

In the living room the remnants of an entirely different decoration were photographed by Ron Henderson in 1969 before they were destroyed during the refurbishment. It was common in the early 17th century to decorate between timbers in a style known as arcading. This was achieved by using a simple carbon black water-based paint on lime-washed infill panels. We are advised that the style is Jacobean. Again, Liese Cattle has expertly re-created the panels (below right) using the photograph as a guide.

|

|

Rising rents

By 1670 the rent to Abingdon Corporation had risen to 30 shillings and it remained at this figure until the house was sold two centuries later. Corporation records show that from this time until the mid-19th century the house was let to an unbroken succession of lessees, whose names we know. However, the lessees hardly ever lived in the house - they nearly always sub-let it to a tenant - so while we know from the indentures the occupations of most lessees, we do not know the occupations of many of the people who actually lived in the house until the late 18th century, when they appeared in local trade directories. (Nor do we know the rent that they paid to the lessees.)

Lessees between 1670 and 1865 were:

John Rice; Richard Hackworth; Mary Jane and Elizabeth Hackworth; Robert Tyrrell senior, yeoman; Robert Tyrrell junior, currier; Richard Clarke, brewer; Nathaniel Bayley; William Spindler, victualler; John Francis Spenlove, brewer; John Moses Carter and Edward Tull and George Bowes Morland (in trust for Mary Spenlove, brewer).

Occupants between 1670 and 1865 were:

Elizabeth Perryman; Nicholas and Richard Hackworth; Robert Tyrrell senior, yeoman; Robert Tyrrell junior, currier; William Tyrrell; Francis Stuchberry, blacksmith; William Keates; William Spindler, victualler; William Mart; Richard Bishop; William Hazell; William Beckingham; William Able (or Abel), hairdresser; Frederick Wiblin.

By 1865 the property had become a public house.

To private ownership

On 11 May 1865 the house, with sitting tenant Frederick Wiblin, was sold by Abingdon Corporation to John Moses Carter and George Bowes Morland for the sum of Ј107-8s-1d. George Alfred Lay, butcher, was a co-tenant with Frederick Wiblin from 1878 to 1887. Morland & Co, local brewers, bought the property in 1888 and it continued to be a pub. Albert Thomas Phipps was the tenant in 1891. By 1894 Elizabeth Phipps was the tenant and she was succeeded in the following year by the Higgs family. In addition to selling beer, William Higgs was a carpenter.

During the four years following 1914, Charlotte Young, daughter of William and Amy Higgs, and her husband Ernest Young were the lessees; Ernest Young was a blacksmith who later worked for MG Cars. The Youngs' daughter, Winifred, grew up in the house and lived in it with her new husband, George Lewis, a chemical engineer, until they bought their own house. Charlotte Young continued to rent the property until the freehold was sold in 1969, though it had ceased to be a pub in 1921. There were also sub-tenants in the cottage which abutted the house at the back, whose names we do not know; sometimes Charlotte also let the downstairs room which had once been the taproom, though Barbara Lee - who rented it for a short while in the 1940s - complained that the whole place was so cold and damp that it made her seriously ill.

From neglect and near collapse to restoration

By 1969 the house had become uninhabitable. Morlands contemplated pulling it down - the site was commercially valuable - Woolworths made enquiries but luckily Jill Ginever bought and restored it. Mieneke Cox examined inside at the time. She reported:

" The house had not long been vacated but was in very bad condition. It smelt of poverty and neglect. The staircase was a death trap, sanitation primitive in the extreme, and in poky small rooms wallpaper festooned the walls in layer upon layer. To restore the house it was necessary to strip it to the beams. It was exciting to view the progress as first the wallpaper and then layers of plaster were removed. Gradually the worst was revealed. One day we were summoned to see the latest discovery; the newel post, a sturdy piece of timber, hanging in the air as its foot had rotted away. The front, too, was almost floating and ready to collapse into the street at any moment. And yet the house still stood, its medieval frame basically intact."A cottage at the back and an outside lavatory, both in very poor condition, were demolished, together with a so-called loft above the cellar; the cellar itself was filled in. In their place a rear extension was built. The restoration of the house was finished by May 1970 and Mrs Ginever Wilson (who had remarried) moved into it with her family. In 1977 it was sold to Bernard and Mauricette Mellor; Dr Bernard Mellor was an academic who had helped to found the University of East Asia. A further extension was added by them in 1981. Since 1997 the house has been owned and lived in by Michael and Gillian Harrison.

Construction and use

The original house had its street entrance at the

southern end of the 20 foot wide plot, rather than at the centre as

it is today. The widening to the south resulted in the

construction of a

two-unit plan, which was common at the time. The change resulted in a

cross-passage running through the building from the front door to the back, and a large

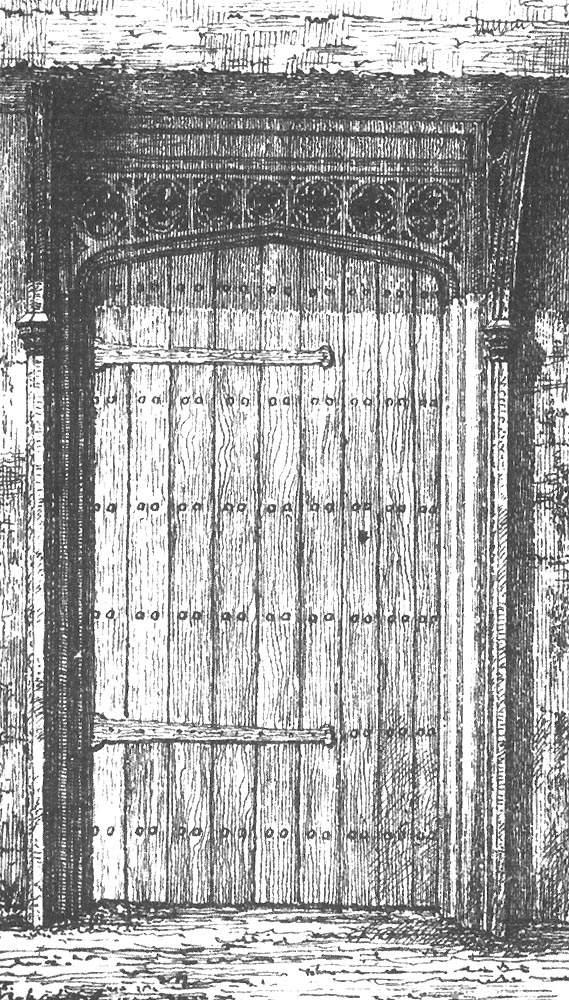

What Pesvner said about No 3 No 3 Stert Street is timber framed and

of pre-Reformation

date. The stone doorway, though, may be ex-situ. The two projecting

gabled upper windows

and the two main gables are probably a 17th century alteration. A book entitled Abingdon in 1644, a lecture by HG Tomkins, published

May 13, 1845, carries an

room heated by a big fireplace to one side

of it, with a bedroom above, and a (probably unheated) smaller room to

the other

side of it with a bedroom above that. This cross-passage was

flagged and

led through the building to a yard at the back. We have been told that

horses were led

along

the passage from the front door and out into the stable in the back

yard. (This

practice went on until the end of the nineteenth century. Straw

would be

laid on the flagstones to muffle the sound of the hooves when somebody

in the

house was ill.) Water came from a well in the

garden.

uncaptioned illustration of a door with elaborate carvings

over the top. Measurement of the present front doorway of No 3 shows an

aspect ratio of 1.66:1 and the dimensions of the illustration's aspect

ratio are 1.64:1. Careful examination has revealed a good match between

the carvings over the door in the drawing and those which have survived at

No 3. Having checked other doors in the centre of the town we conclude

that the illustration is most probably of an earlier front door to the

property which was replaced as late as the 1960s.

uncaptioned illustration of a door with elaborate carvings

over the top. Measurement of the present front doorway of No 3 shows an

aspect ratio of 1.66:1 and the dimensions of the illustration's aspect

ratio are 1.64:1. Careful examination has revealed a good match between

the carvings over the door in the drawing and those which have survived at

No 3. Having checked other doors in the centre of the town we conclude

that the illustration is most probably of an earlier front door to the

property which was replaced as late as the 1960s.

The jetty

The first floor was originally jettied out over the ground floor. In early twentieth century photographs there is no jetty visible - the ground floor frontage is virtually flush with the first floor. We do not know when this happened nor who did it and why. It is unlikely to have been possible before the Stert river was culverted in 1794, so our guess is that it was done soon after the culverting in order to enlarge the downstairs rooms. Once the building started to be used as a pub, the larger downstairs room became the public room and the smaller the parlour for the family; the enlargement would have made this arrangement more comfortable. Customers could continue to bring their horses through the house and stable them in the back yard. This pattern of use suited the two-unit plan and continued until it ceased to be a pub after the First World War. The concealed jetty was not discovered until 1969, when it was restored and the ground floor front wall underneath it was rebuilt in its original position.

The several names of the public house and a theft

By 1842

it

had become The Golden Cross (shown left in 1921, the year in which it

ceased to be a pub) and by 1857 it was the Butcher's

Arms, probably because at least some of the tenants were butchers as

well as

beer

retailers. By the end of the nineteenth century the name reverted to the

Golden Cross, although many locals continued to call it the Butchers'

Arms.

By 1842

it

had become The Golden Cross (shown left in 1921, the year in which it

ceased to be a pub) and by 1857 it was the Butcher's

Arms, probably because at least some of the tenants were butchers as

well as

beer

retailers. By the end of the nineteenth century the name reverted to the

Golden Cross, although many locals continued to call it the Butchers'

Arms.

In January 1861 Jackson's Oxford Journal tells us that one "James Pearce, late in the Abingdon Police, was charged with stealing a shovel, the property of James Collier from the Butchers' Arms public house, where some repairs were going on; remanded". (We don't know the outcome).

Major construction changes

Over the centuries other additions and alterations were made, though generally speaking we do not know when they happened and can only guess why. The cellar with a loft above it was added to the back of the house and used to store beer. The cottage (which existed in 1854 and possibly before) abutted them. At some time also the ridge roof acquired four gables; one can still see the alterations to the structure of the roof which had to be made to accommodate these gables and the place where an internal door was inserted, probably to enable the roof space to be turned into bedrooms. Perhaps this was done to increase the number of rooms to be let - certainly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the building is listed in local directories as an inn.

The back of the house

Until 1969 the cottage at the back of the house was sub-let and had the only cooking facilities for the whole property - what is now the kitchen was the wash-house. Until after the Second World War there was gas for cooking but no electricity at all - even when George Lewis installed it for lighting in 1946 it was only on the ground floor. The outside lavatory in the back yard served the people in the house and in the cottage. That and the sink in the wash-house were latterly the only sources of water - the well in the garden does not seem to have been used after mains water came to the town in the 1870s.

The Stert stream

Early leases show that lessees were forbidden to thatch the house - presumably because of the risk of fire. They also undertook to keep in good order the arches over the Stert stream which ran in an open course immediately in front of the houses on the east side of Stert Street, dipping under St Nicholas' Church and joining the Thames by the bridge, as it still does. It had wooden and later brick arches or bridges over it so that the inhabitants of the houses could reach the road on the other side. The river was culverted in several stages; the final stretch - which was in front of No 3 Stert Street - was completed in 1794. (Evidence of the arches/bridges can still be seen from within the culvert.)

Acknowledgements

We are much indebted to Jackie Smith, honorary archivist for Abingdon Town Council, whose advice and help over many years has enabled us to put this history together. Also our thanks to the Young family who provided much material relating to the 1900s and to Peter Higginbotham, who helped us to construct this web page.

************************************

We should be pleased to hear from anyone interested in the history of this part of the town. Spam prevents use of our email address here but we are in the Abingdon phone book. Our address includes OX14 3JF.